THE STARR 1858 DOUBLE ACTION REVOLVER

A little piece of history...

Although it encountered but little success among its users, the Starr DA revolvers - as well as the later SA versions - have undoubtedly played an important role in the Union Army armament during the American Civil War. With a total of over 21.000 revolvers, the Starr Co became the third most important arms supplier to the Yankee Army, after Colt and Remington.

The inventor Ebenezr Starr was born on August 16, 1816 in a rich family known for their lobbying and numerous commercial transactions with the American Government. Since the 1790's, the family had been an important supplier of accoutrements, military cutlery, sabels, lances and pikes, but also common tools such as shovels, axes and hammers, which they generally ordered from various producers.

Ebenezer's father Nathan, however, was an armsmaker and had sold over 20,000 flintlock muskets to the Army between 1831 and 1845.

Ebenezer studied armsmaking and acquired commercial skills in his father's factory. Highly interested in the then still new technique of the revolvers in general, he was firmly determined to elaborate and produce a revolver that would proove superior to all others by its technique as well as its improvements.

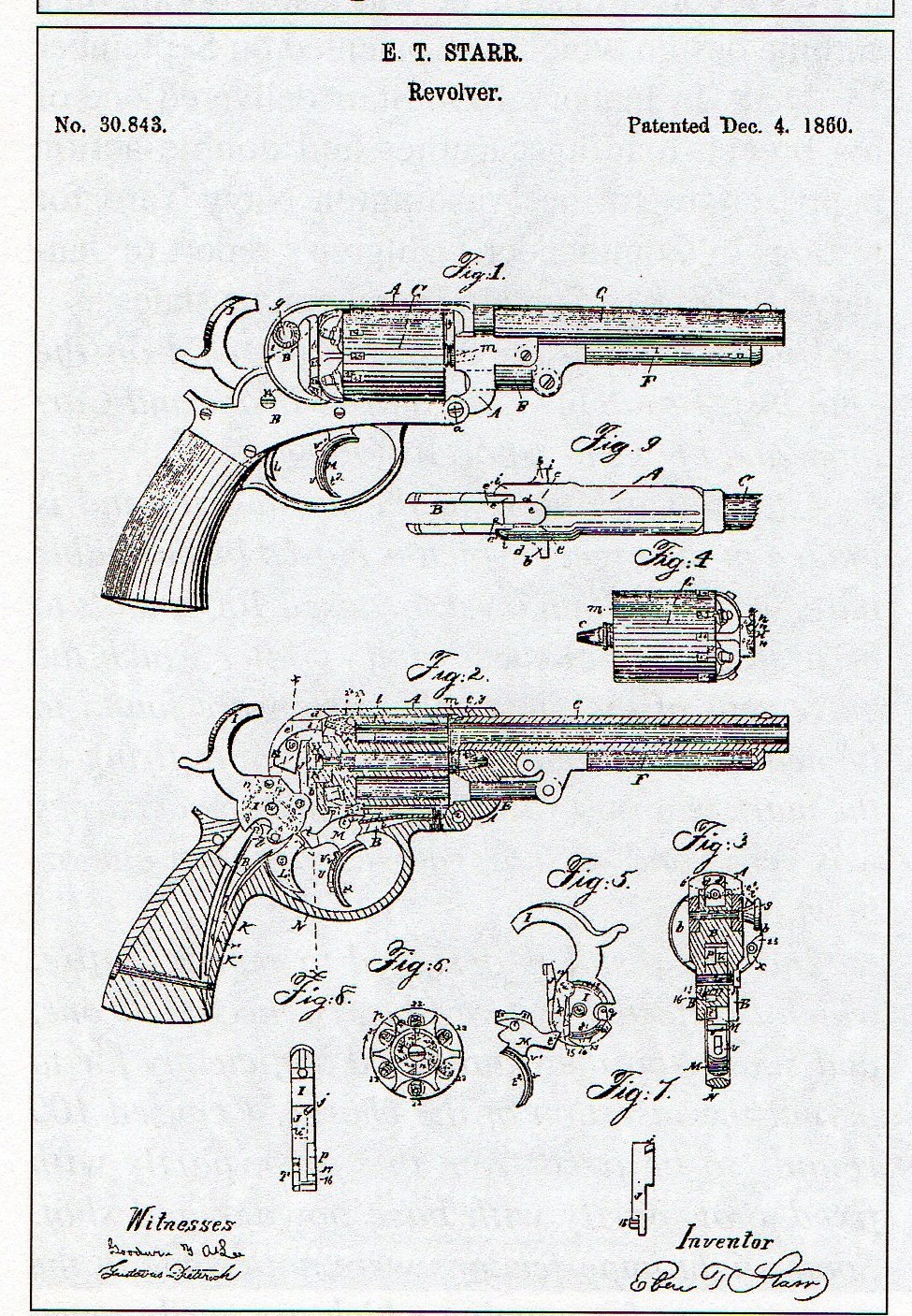

On January 15, 1856, at the age of 40, Ebenezer was granted patent n° 14.118 for a number of improvements on "revolving pistols". He invented a percussion double action pepperbox featuring a special internal cocking lever and an adjustable trigger. That last concept would be later adapted for use in his revolvers.

His first double-action revolver was issued in 1857 and was of .36 caliber. Except for the cylinder which was noticeably longer, the revolver was identical to the heavy .44 caliber revolvers that were produced later on.

The new gun underwent heavy tests at the Washington Arsenal and was finally rejected because of malfunctions. In his January 21st, 1858 report, major William Bell stated that the new weapon offered many advantages, among others the high firing speed, but that its .36 caliber was too weak; also, a number of improvements had to be taken into consideration, the most important being a cap release groove, for some exploded caps misformed and jammed the cylinder. Besides, those exploded caps proved very difficult to remove.

Meanwhile, Ebenezer was working on a new carbine - that would later considered superior to the Sharps by the Army command - as well as on his second revolver, which was to be in .44 caliber.

The modified and improved .36 revolver was finally accepted by the Ordnance, against Inspector John Taylor's recommendations. At the beginning of the Civil War in 1861, the Ordnance first ordered 500 revolvers, soon followed by 1,250 additional.

On December 4, 1860, Starr was granted patent n° 30.843 covering the improvements brought to his revolvers and included in its .44 caliber version.

Some reports and letters leed to think that the head of the Military Ordnance, possibly "supported" by other arms suppliers, were opposed to the purchase of Starr revolvers and highlightened all their weaknesses; other officials, however, possibly more careful because aware of Starr's excellent relationships with the political world, proved much more open.

On August 31st, 1861, the company's chief accountant Everett Clapp sent the Ordnance Superintendent Colonel Ripley an offer for 12,000 revolvers in .44 caliber, available from stock at the price of $25 each. Ripley accepted the offer on 23rd September but demanded that the price would include a screw-driver, a nipple wrench and a bullet mould for each gun. On January 11th, 1862, Ripley increased his order up to 20,000 units.

Apparently however, the contract was re-examined by the Holt & Owen commission during the spring of 1862, and the total order reduced to 15,000 units at the price of $20 a piece. Finally, Starr delivered 13.100 .44 caliber revolvers over a period of 11 months.

In order to stop the discussions between pro and contra's, the Navy decides on March 18th, 1863 to submit the revolver with serial number 9002 to very heavy endurance tests. According to Second Commander Skerret, the revolver fired without interruption 500 Johnson&Dow combustible cartridges designed for the Starr, followed by 60 Joslyn cartridges and finally 362 combustible cartridges designed for the Colt 1860 Army. There was no misfires and the the revolver didn't even need to be cleaned. Convincing demonstration.

THE REVOLVER AND HOW IT WORKS

The .44 caliber Starr DA is a big percussion revolver with a size and weight comparable to the Colt Dragoon. It is ugly and repulsive, difficult to handle, but also very impressive. Weighing a little over 1,3 Kg empty, it is obviously one of the most imposing revolvers of its time.

The cylinder has six chambers which are longer of the Colt Army's, although the cylinder was made noticeably shorter than the previous .36 calibers.

The large sized grip with its well-developed spur provides a firm handgrip, but the very "high" structure of the revolver and its weight contribute to weaken the balance. This revolver is definitely not destined to delicate ladies hands.

The barrel has 5 grooves to the left, without gain twist.

The revolver features two different safety systems, the most important being double locking notches in the cylinder like on the Manhattan Arms Co' revolvers; the second one is the classical half-cock notch in the hammer. That notch is cut far rear in the hammer body, so that the latter has to be pulled only a few mm backwards to engage it, which is enough to loose contact with the capped nipples but not enough to increase the risk of jamming in the clothing.

The trigger block features two cylinder locking cams, which means that the cylinder is always locked in position regardless of the inclination of the foretrigger.

However he basically had conceived his revolver as a functional war tool, Starr did sell a few luxury versions of the weapon to the civilian market. These scarce exceptions are all profusely hand-engraved and inlaid, the engravings are of high quality, and the grips are always made of precious wood or other luxury material.

Very few standard models have found their way to the civilian market, though. Most of the revolvers are marked on both sides of the grip with a cartouche containing the Army Inspector's initials.

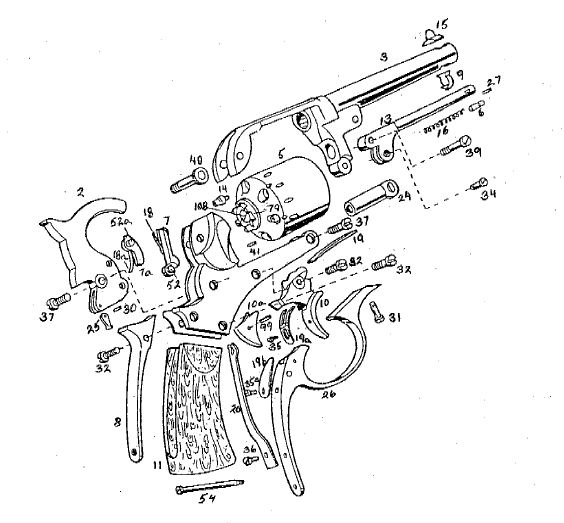

The Starr DA differs from all other revolvers of its time in many conception details:

- Very complicated inner mechanism

- Closed frame but with a topbreak barrel that turns on a hinge located at the fore bottom of the frame, ahead of the cylinder (like on the later 3rd Models Smith & Wesson). That system allowed for a quite fast replacement of an empty cylinder by a full one. In closed position, the barrel is secured by a large transversal pin, which can be unscrewed by hand...and easily lost in combat situation or while riding a horse.

- A double trigger: the large foretrigger only cocks the hammer and turns the cylinder. Behind this trigger, in the very back of the guard, is a second trigger lever which is connected to the hammer through the sear. That second trigger is the actuated by the first one in the double-action mode.

- The revolver does not allow conventional single-action operation, for it is impossible to cock the hammer with the thumb. The user can only pull the hammer into the halfcock position but cannot bring it to full cock without using the trigger.

However, the double-action mode can be divided into two distinct phases:

On the rear face of the foretrigger is a small slide with a pin in the middle. When the slide is pushed upwards and the trigger squeezed, the small pin engages an opening in the frame and has in fact no effect at all. The foretrigger pushes the back one and the hammer falls down.

Double-action shooting requires a quite muscled finger, for the trigger is very hard to squeeze.

By squeezing the trigger carefully, the hammer can be locked in the fullcock position. The user can take his aim and fire the revolver by simply pressing the trigger a little further.

In the event the user needs a more accurate shot, he can push the small slide downwards. In that case the pin will come against the frame, blocking the course of the trigger right at the time the hammer engages the full cock notch while the cylinder is perfectly in line with the barrel. In order to fire the revolver, the user must now press the back trigger separately.

Questions can arise about the utility of this curious configuration, which would rather be expected on a sporting weapon than on a heavy military revolver.

I have on hand two of these impressive guns, both showing traces of intensive use. Both are perfectly working and show no play at all in the cylinder nor the hinge despite 160 years of war and adventures.

At this point I must have a thought for the adjusters of all gunshops, whose names are always forgotten by History. With their files, sand clothes, self-made scales, all their secret pieces of wood and iron but in the first place with their eagle eyes and their skills, have realized those perfect timings and alignments that made a good weapon perfectly reliable in a time life without weapons was unthinkable.

Few people can imagine the difficulty and precision of that work, that can only done by hand, and that guarantees that a hammer engages the full cock notch at the very moment one of the cylinder chambers is perfectly in alignment with the barrel and the upwards moving locking cam engages the corresponding notch without even scratching the cylinder.

Although the revolver has an attached loading lever, it is far easier and faster to reload by replacing the empty cylinder by a full loaded one as exposed before.

Since the trigger block has two locking cams, respectively at its for and back ends, the cylinder is always locked in position, whatever the position of the trigger might be, which means it cannot turn freely.

In order to reload using the loading lever and without removing the cylinder, the user must first bring the hammer to halfcock; in that position, holding the trigger squeezed a little bit, allow for both locking cams to disengage, so that the cylinder can be turned freely. This procedure can be relatively easy if using combustible cartridges; however, it will be quite difficult to load the revolver that way in a combat situation, with cold fingers, if the user has to reload with loose powder and balls.

So despite its strength and undiscutable qualities, the Starr DA still has numerous weaknesses that are probably the cause of its low success among the troops it was issued to. In the course of 1863, it would be replaced by a new version in single-action, with a longer barrel, that would be much more appreciated.

Anyway, Ebenezer Starr has reached his goal, which was to provide the Army a totally new and different revolver.

Marcel

Star 1858 Army DA

I send pictures of a Star 1858 Army DA revolver. It might be of interest to contrast this one to the Belgian cartridge converted gun presently shown on the site.

It is interesting that unlike the 36 caliber Star Navy model, the 44 caliber Army model could be fired either single or double action.

However, if cocked for single action fire, it was necessary to pull the small lever behind the trigger to gently release the hammer without discharging the weapon.

Roger